KATC Meteorologist Jobie Lagrange visited Hamilton Hall to give a guest lecture about hurricanes for students in Int

Interview with Jim Bollich, 101 Years old alumn

Wed, 09/14/2022 - 12:50pm

Jim Bollich, 101 Years old, Bataan Death March and Japanese Prison Camp Survivor, and 76 Years a Geologist: An Interview for the School of Geosciences at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Jim, We came to know about your life story through an article in the “The Acadiana Advocate” (August 15, 2022). Googling “Jim Bollich” led to several highlights of your history. You have published a book about your military experiences. There are many sources of information about your capture, punishment, and imprisonment in World War II.

We are interested in your life as a geologist. Your post high school education began in 1938 when you left the farm where you grew-up in Mowata, Louisiana to take classes, in Agricultural Engineering at Southwestern Louisiana Institute (SLI). The program has now become the Environmental Science Program within the School of Geosciences at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (UL Lafayette).

You enlisted in the military in 1940, were posted to the Philippines, survived the Bataan Death March, and endured Japanese captivity in Manchuria. Please tell us about your educational experiences, career in geology, and advice for today’s students.

PRE-WAR STUDIES

When I left the farm to attend college at SLI (Southwestern Louisiana Institute) in 1938, it was through a federal program called the National Youth Administration, It Paid $30 dollars a month, and $18 came out for room and board at the school, leaving the rest to buy books etc. The only problem with the program was the work schedule, which was 8 hours a day, 3 days a week. That meant that I could only take 9 hours a semester. Another requirement was that I had to major in agriculture, so I selected Agricultural Engineering. I had no intentions on ever staying on a farm, but I had no choice but to stay in agriculture. I stayed in school for 3 semesters and left to join the US Army Air Corps in August, 1940 because it looked like we were about to go to war and I did not want to be drafted.

POST WAR YEARS

After being away for over 6 years, I finally returned to SLI in the Spring of 1946, but this time under a different program known as the G I Bill, which paid me $110 a month, plus all other expenses such as books, supplies, etc. What a change. I no longer was required to take agriculture, so I selected Business Administration, although I found it dull and uninteresting. Fortunately, I had a room-mate who was taking courses in geology, a subject that I knew nothing about, but really caught my attention, so I also started taking such courses. I was hooked, but the school did not offer a degree in Geology, and which was associated with the Geography Department, with only two professors, one for Geography and one for Geology. The geology courses as I remember were Geology 101, I believe, then such others as geomorphology, petrology, minerology and minerology. I enjoyed every one, but continued in Business Administration, finally graduating in 1948 with BS in that subject. Then I discovered that the geology students were going on a field trip conducted by the University of New Mexico (UNM), so I decided to go with them. It was a wonderful experience, because now you could see the real thing that was taught in college with books. I enjoyed every minute of the field trip, was sorry to see it end and I returned to the flat lands of south Louisiana. But, not for long, because within a few days back home I received a letter from the UNM Geology Department offering me a scholarship if I returned. I did not respond immediately because I could not make up my mind about continuing with my education or to start looking for a job in business, because I had reached the age of 27 and was broke. Then came a second letter, and I felt obliged to reply. It was only then that I decided that I would continue with my education in Geology, get a PHD degree in Geology and become a college professor.

UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO

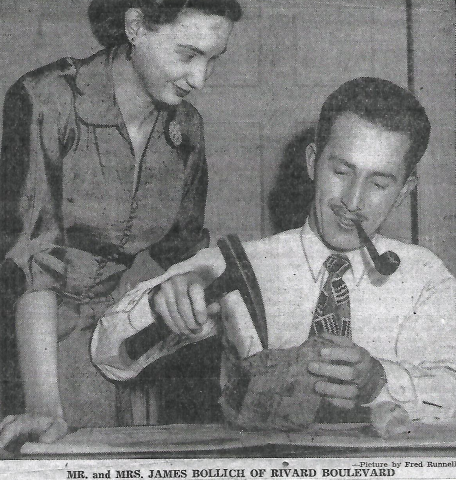

Upon returning, I was given the job of Instructor in the mineralogy lab. The Geology Department was so much larger than what SLI had, with four professors and many courses to choose from. I was in heaven. It was there that I met my future wife who also had a scholarship, and was working on an MS in Geology. She was a semester ahead of me, and left for a job in Washington, DC working as a geologist for the Military Branch of the USGS. I finished the next semester. After we were married, I started working on my thesis for my MS. It was a sedimentary study of sand grains along the Atlantic coast off the coast of Maryland, with research at the Library of Congress. At the time, there was some question as to the cause of the difference in shape of sand grains; was it water worn or caused by the action of the wind on the grains.

Then one day my wife said, “If you are planning to earn a PHD in Geology you do not need an MS in Geology. Do as your brother Charles did. Skip the thesis and start on your PHD”. I went for her suggestion and was preparing to go to Syracuse University when everything changed again. Living in DC at that time was horrible, and when I was nearly hijacked by two men when I was working at the Library of Congress, I decided to move out west again for my education. I choose the University of Wyoming, at Laramie.

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING

I was in God’s country again, and where everywhere you went, it was like an outdoor classroom in Geology. I had something called the President’s Scholarship, and my job was to teach a course called Geology for Engineers. My wife had a job working in a research section of the University. It was near the end of my second semester when I noticed on the bulletin board something about a Fulbright Scholarship. It intrigued me, and I saw it as a possible way to study the geology of some other country. I was going to apply, just for the hack of it, knowing that it was probably a waste of time. Applications were available, so I filled out one, outlining the project that I had in mind, which I knew was probably the most important part of the application. When I went to get application forms, I was told that there was at present a geology student in Ireland, I believe, on a Fulbright Scholarship who had just left a semester before I arrived. The person said that I would have a better chance if I submitted my application through the University of New Mexico. I knew that he was right, but I turned it in from the University of Wyoming anyway, not expecting to ever hear back from it again, but I was wrong. Within a few weeks I received word from the State Department that I had been awarded the scholarship, and I was to report to the University of Queensland, Australia within two weeks. My flight ticket was on the way. But the semester at Wyoming had not yet ended, so I had permission to leave early. The only professor who made me take a final exam was my economics professor of all people.

This is a summary of the program that I submitted for the Scholarship, and it was also approved by the Geology Department for my PHD dissertation. I called it First Cycle Sedimentation. I mentioned that most of the rocks that a geologist studied probably went through many cycles of erosion, transportation deposition, and change and I wanted to see what happened at that first stage. The university had a geologic map of Australia which I based my program on. It was a large granite area where a large river started at its interior and ended up several hundred miles away in the ocean of southern Australia. But my dream ended about the second day after I arrived at Brisbane University. I met with the head of the department, and he wondered how I had come up with my program and I told him about the map of Australis that we had at Wyoming. That’s when he began to tell me that that map was not necessarily correct because of its remoteness. He said that I would go there and find it entirely different from what the map showed. He admitted that the map was probably made by geologists sitting in their offices, and assuming what the geology was for that area. No one would go to such an isolated place anyway. Then he went on to say he wondered why I was sent to Queensland, on the east coast of the continent, when my study area was near the west coast, hundreds of miles away. He even went further to say that even if the place was exactly as I thought it was, I would need to carry all of my supplies with ne, which included water, food, shelter, and in such a quantity that it would require the help of several people, and some form of transportation. By now, I was definitely convinced that he was right and my program was doomed. He then proposed a program closer to home that involved the study of sediments in Mortan Bay, a body of water about the size of Vermilion Bay. That is what I ended up working on, but the facilities were so limited in their university that in my mind that work was useless. But I did not give up. In the meantime I was playing with an idea that involved mountain building. At the time, theories varied, and one was the shrinking apple theory, and the theory of isostasy, which I never believed in to this day. The University had a good science library and I was able to work on my theory which I titled, Relationship of Magnetism, Gravity, and Atmospheric Electricity to Tectonics. I showed it to the head of the department and he arranged for me to present it at a meeting of the Royals Society of Queensland, a society composed of mostly scientists of all disciplines. It was indeed an honor and the only negative question asked was, “Don’t you think that after such a long time, equilibrium would have been reached?” It won’t be reached until the earth has cooled to where there is no longer a molten interior, which is something that we do not have to worry about. The moon would be an example of what I had in mind. So my stay in Australia was not wasted after all, even though I did not return with my original project.

While I was in Australia, I received a letter from the Geography and Geology Department at SLI asking me to visit the school after I return to the states. I did that, and the reason for the visit was an offer to teach the geology courses because the present teacher was leaving to work for an oil company in Houston. I, of course was greatly honored by their offer, but did not commit at the time. I had been in school so long that I wanted a short rest before resuming my studies again. Another concern was; a one man Geology Department, and why was the present professor leaving? I turned the job down, and decided to look for work for a while before going back to Wyoming. I ran into my room-mate who got me into Geology who was now employed by an oil company, and he told me that Tidewater was looking for a geologist. At the time all of the oil companies were downtown. After talking to the District Geologist at Tidewater he said that I could go to Houston and talk to the people there, but he was afraid that I would not be hired because I had too much education. The company would hire me and I would leave them in a year or two. I did get the job and I did leave them after 3 years, when approached by Tenneco who doubled my salary. By then I so enjoyed the work as subsurface geologist that I abandoned my idea of further study. Tenneco was such a good company that I stayed with them until I retired in 1986 at the age of 65.

WORKING YEARS

The part of the work that I liked most about my job was interpreting the subsurface geology of the Gulf Coast region in search of prospects capable of containing hydrocarbons. Before long, if the information was available, I had worked ever producing field in South Louisiana. I started as a Senior Geologist and held most jobs, ending up in my final years as a Senior Consultant.

The beauty of my job was that I was doing work that I really enjoyed, but still doing a lot of teaching of geology aside. I gave a course in Subsurface Geology to all new, beginning geologists, as well as to the geophysicists, geological engineers, drillers, secretaries, and even to some service companies with permission from Tenneco. I also went overseas to evaluate large concessions as to their merits. The material that I used as an instructor at Tenneco is the material that I used for my unpublished book. If I ever had to decide on a profession again, I would definitely go back to geology. I no longer travel, but I keep up with all aspects of science. There are still so many questions still to be answered.

ATTRACTING STUDENTS TO GEOLOGY

Under the present situation, I know that this is a major problem, especially as it pertains to the oil business. At one time in the past, exploration geologists could pick and choose jobs and companies to their liking, but I am afraid that that time is past and will not return. You know as well as I that this country cannot exist without petroleum, but there are so many environmentalists who believe that it can. They are wrong.

As I see it, the best time that you have to convince students to continue in geology is when they are taking the introductory geology course. Many, as you well know, only take it to fill a requirement for their science credits, and then go no further. Some way, at that time, they have to be so impressed by the subject that they take it as their major subject. It is a pity that Lafayette is so far from geology that can be seen, as well as studied in books. Taking them to see deltas or salt domes will not work. Sometimes looking at many types of fossils might help, or at the many different types of crystals, during that first course. Showing slides of structures to go with their book is a possibility. These can be to show the beauty of the outdoors that goes with the subject. Even ask the students to bring pictures that they might have taken on vacations to share with others. Don’t necessarily stick to the book. A test or assignment might be to draw a fossil of their choosing, describing its type and age. I know I always was looking for Trilobites while doing field work, but never found any until I went to a place in Utah where you are guaranteed to find some. I am not sure if a lab went with that first course in geology, but if it did, it should also be made to be interesting. As well, in the past, some may have been drawn to Geology because of the good pay given by oil companies, but there are other good paying jobs for a geologist besides looking for oil. I know some in the industry are referred to as soft-rock geologists. Some schools concentrate on one or the other of soft-rock or hard-rock geology. UL probably still may be pushing soft rock geology because of the oil business. If it is, perhaps it should give more attention to other aspects of geology.

Looking back, I probably would have been satisfied with such work as looking for commercial minerals, mining, etc., but, I am sure glad that I ended up as an exploration geologist. It was such an interesting and challenging career. There were many ups and downs during my career, but, fortunately, I was never affected by any. After my time in the service, I was satisfied staying in one place that I knew and considered home, and that was Lafayette, and the company went along with that outlook.

Today, my only contact with the oil industry is through a friend who is still involved with drilling and current operations. My greatest surprise came when companies started producing oil and gas from shales. When we reached shale, with no possibility of encountering sand again, the well was shut down. Looking back, there was evidence that shales contained hydrocarbons, by their resistivity, but they were of no value because of very low permeability.